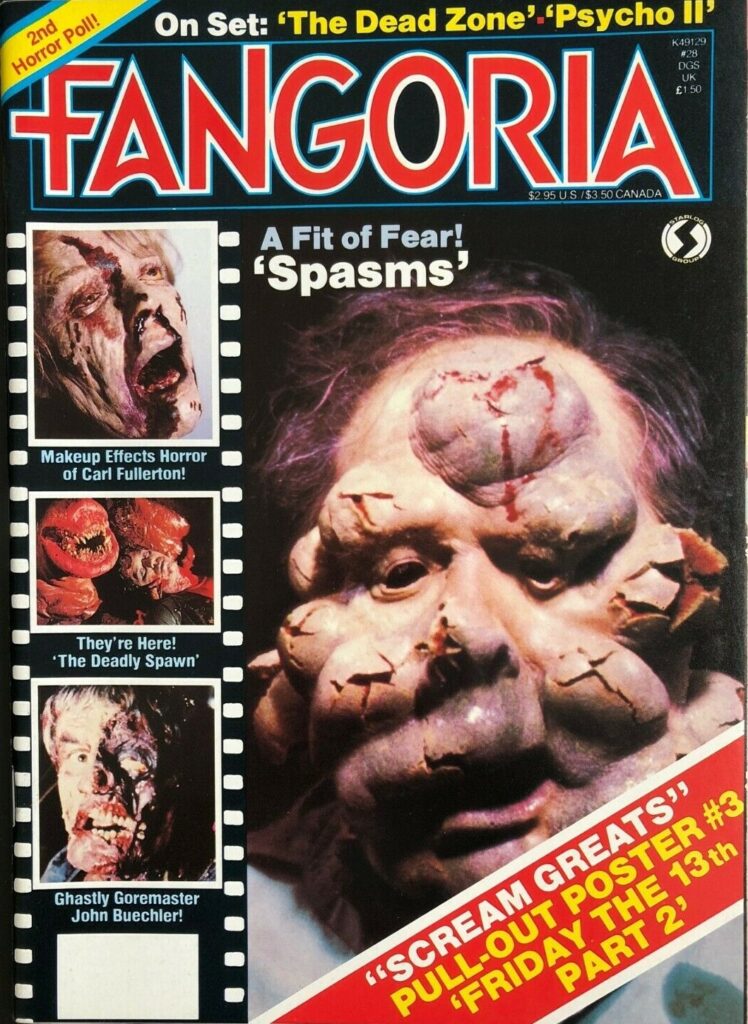

When we set out to start the Crestwood House show my two co-hosts and I wanted to do something a bit different than all of the horror film podcasts that dot the landscape (that tend to cover “up to the minute” releases or almost strictly 70s movies and beyond.) There aren’t as many classic horror shows floating around, so we figured we’d have some room to dig into the wealth of films made from the turn of the 20th century up to the point when horror changed into what we’d now call modern. I was recently digging through all of my old back issues of Fangoria, Hammer House of Horror, and Famous Monsters of Filmland looking for articles about the movies we’ve chosen for our first two seasons when I happened upon an article in the July, 1983 issue of Fangoria (#28) by William K. Everson (author of many film books centering on the golden age of cinema including Classics of the Horror Film) that really digs into one of the challenges of being a lover of and podcasting about classic horror.

There are a number of reasons why it can be hard to “crack the nut” of classic horror. First and foremost is the idea of trying to place oneself in the period in which the original films were presented, to get into that headspace. Not only are the most stark and obvious differences a hard gulf to cross for some, like black & white versus color films, or the prevalence of stage acting over the more naturalistic method acting that because more common in the 60s, but there are the societal differences between gender or race opportunities. For a more modern audience weaned on final girls it can be difficult and weird to accept women in vastly different and way more misogynistic roles a lot of the time. And don’t get me started on all of white casting in ethnic roles, egads.

But, as someone living in the 21st century it can be hard to parse out the extremely different place that horror itself occupies in our lives now versus in the 1930s for instance. Audiences were not prepped for horror the way that we are today. There was not a constant influx of horror in entertainment, and it was still a sort of devious and novel genre. We have to remember that monsters, especially Vampires, Werewolves and walking Mummies were not as common prior to the Universal film boom, and that seeing them on theater screens was actually shocking to some. Sure, Stoker and Mary Shelly’s novels were popular, but we have to remember that in a pre-television world where talkie films were still relatively new, pop culture just didn’t have as much of a place in the general audience’s lives. It must also be noted that the true horrors of the real world were largely absent from most folks’ lives in the 30s. For sure there was strife, the great depression held a lot of families in the grips of poverty and there was for sure racial strife in most areas of the country, but there was enough distance from vivid horror of the Civil War and the vile imagery of WWI did not permeate the culture like the newsreel footage from WWII and Korea, not to mention the eventual television broadcast of atrocities from Vietnam to inundate the populace with true horror. This is all stuff that we tend to easily forget before slipping in a VHS copy of Dracula or Mad Love. It’s a big ask to get modern audiences to think about this stuff when they’re looking for entertainment.

That said, the basic gist of the piece is about the merits of classic horror and that in the burgeoning new age of more violent and gory films, a key element of the genre was being lost, that of subtlety. Now, Everson was far from deriding modern horror at the time, he goes to pains to talk about films like Poltergeist and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre that he adored, but you can clearly see that he seemed to be troubled that a long-standing form of the genre was being eschewed for a focus on effects heavy movies that shock the audience in the most obvious and visceral ways possible.

Again, Everson strongly stresses the importance of subtlety to the genre in his article. For one, there are a lot of subtle thrills or moments of terror in the golden age films, moments that are easily ignored when these films aren’t presented in the context of the theatrical experience they were designed for. Again, so many of us came to these films through television matinees or home video rentals. We’re in the comfort of our living rooms being bombarded by commercial interruptions, the pull to grab a snack out of the fridge or, just plain old daylight. So many of these movies were designed to be seen in dark theaters with little to no distractions beyond the pop corn or the folks next to you. When you’re staring up at the 30ft tall visage of Karloff’s Frankenstein or the giant bald head of Peter Lorre in Mad Love you’re rapt and the slight things, the subtle glances or lingering camera shots have more impact.

“The shared excitement of a subtle thrill in a packed theatre is something that has almost been forgotten now.”

It underlines the idea that some films who do have reputations for being gore-fests, actually are masterfully trading on subtlety like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre which showcases a couple, almost harmless instances of actual gore (the exhumed bodies shown for split seconds set to camera flashes in the opening and the hitchhiker cutting his own hand) when the later brutality is largely suggested and cuts away letting the mind’s eye fill in the actual gore. I would counter and argue that the suggestions TCM make and what they do show (bodies hanging from meat-hooks, the bone furniture, and the clubbing of a character from afar and his twitching body afterwards) are so disturbing that they might as well be given space next to gorier fair like The Evil Dead or Dead Alive. At some point, seeing the knife slip inside a body and the blood rushing out is as gory as the suggested variation if shot well and tense (think of the scene in Saving Private Ryan where Adam Goldberg’s character is wrestling with the Nazi.)

That said, I think the author is onto something in that leaning on the mind’s eye can be just as frightening or even more so than outright showcasing gore. But the trick with appreciating this is in letting older films draw you in. Attaining this focus can be hard, especially in today’s world that is rife with distractions that will instantly draw you out of a film. It’s compounded with the fact that older films can come off as quaint, either because they were filmed to be considered modern at the time and that in and of itself has become quaint, or because the films were self-censored to ensure the largest possible audience. It’s not that it’s supremely hard to envision life in the 30s, but the life depicted in the 30s minus characters speaking or acting realistically/more naturally is a barrier to entry for a lot of people.

Lastly, the author posits the idea that he would rather not try to imagine a future where the current crop of early 80s flicks were no longer the height of gore and violence. The inference is that he couldn’t imagine a world where films became even more vile. He wonders what fans would make of The Evil Dead 30 years from it’s release. So he was correct in noting that film would continue to get more and more violent and cold-hearted. The subtlety would be thrown out of the window for extreme realism and effects work. He was describing the era of torture porn of the mid to late aughts. The fact that The Evil Dead is now considered a cult comedy classic that just happens to dwell in the horror genre might also floor the author had he still been alive to fully see the film blossom into a favorite.

Luckily, we’re reached an apex of gore and violence where movies existing just to explore these ideas are becoming passe. We’ve retracted a bit and are now falling back heavily on subtlety, so if there is one takeaway from this article it’s that even though it took another 40 years, we’re finally trading in subtlety again. So maybe it is a good time to seek out some films from the golden era, turn off all the lights in the house, put down the cellphone, and focus on the nuances of films that are almost a century old.

If it helps with future research, I’ve got a pretty good sized digital Famous Monsters collection.

Thanks sir! We have a decent sized collection, though in digging through it I’ve noticed that the magazine was kind of odd. It seems like 70% of each issue is dedicated to either abridging the stories of horror films or posting random photos. There’s little in the way of commentary. I was kind of shocked actually. Granted, I know at the time those wordy movie synopsis were important as there was no home video market, and little access to the films outside of TV, but it’s kind of a bummer now when I’d rather read about how the fans and academics felt at the time…